The Rebirth of the Paywall and Why That is a Good Thing

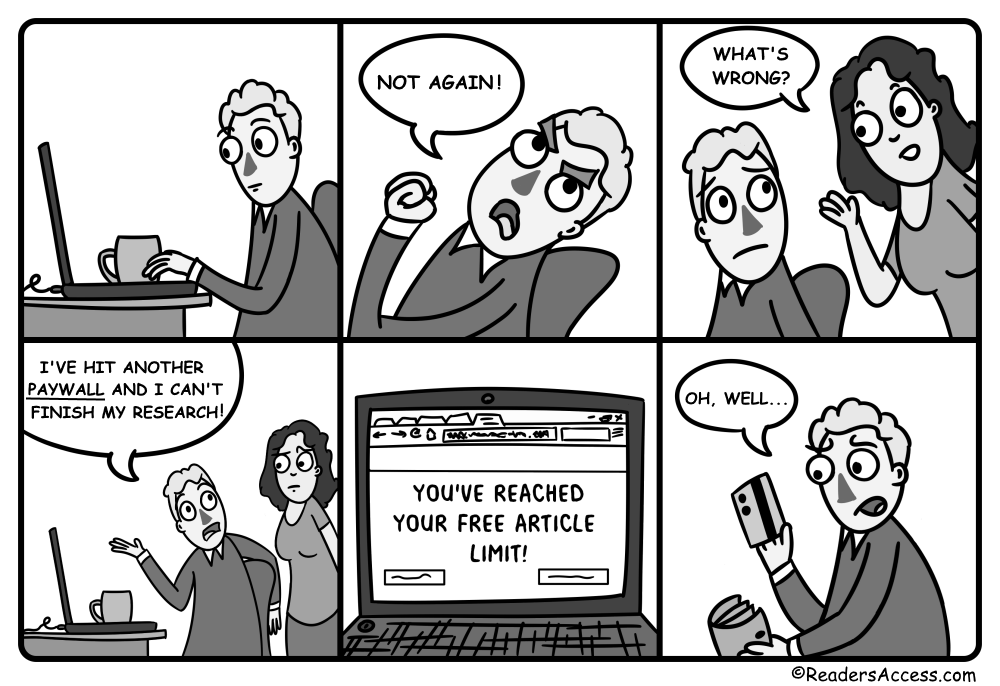

For the past decade or so, news outlets around the globe have suffered a significant decline in advertising revenues and paid print readership. This has led to the rise of paywalls – a method of restricting access to digital content via a paid (usually monthly) subscription.

It was Microsoft who first tinkered with paywalls in 1996, after they launched Slate, an online-only magazine, and charged readers $20 annual subscription fee. The Wall Street Journal followed soon, in 1997, to become the first national newspaper to erect a paywall. Despite maintaining a paywall for more than 20 years, the WSJ Online remained one of the most widely read online newspapers, acquiring over 1 million dgitial-only subscribers by end of 2016. Other media outlets followed in tow, including The Times (London) who implemented their paywall in 2010. Paywalls are also common in academia, where readers can access research papers by either paying a monthly subscription or buying a one-time access to the paper.

Interestingly, following the initial widespread implementation of paywalls, many companies decided to abandon them. The New York Times lifted their $35 monthly fee for overseas readers in 1998; the Los Angeles Times dismantled theirs in 2005, only two years after they first began charging for monthly subscriptions. The reason for the abandonment of the paywall was simple: budgeting. After the initial implementation of monthly subscriptions, the Los Angeles Times reported a whopping 97% drop in readership. Archant’s senior executive Stephan Phillip called the implementation of paywall a ‘complete disaster’ and said their company would never consider putting it up again.

Despite critics like Arianna Huffington declaring paywalls to be history in 2009, more and more companies have started bringing their paywalls back up. The Atlantic was amongst the first to take down their monthly subscriptions some 10 years ago. In December 2017, however, they announced they would be launching a metered paywall in 2018, granting readers access to 10 articles for free per month.

The Atlantic's decision makes financial sense: when they first took down their paywall in 2008, it was an attempt to grow their digital audience and advertising revenue. In 2017, their readership reached the astonishing 20 million – a 20% increase since 2016 – and charging for monthly subscriptions proved a better revenue source than relying on advertisements alone.

The rebirth of the paywall is in a sense a response to consumers’ increasing willingness to pay for digital content in a similar fashion as they do for services like Netflix and Spotify. The proportion of Americans paying for their online news jumped from 4% to 18% between 2016 and 2017 alone (Reuters Institute Digital News Report, 2017).

Of course, there have been critics of the change. The co-founder of Wikipedia called The Times’ decision to re-adopt paywalls a “foolish experiment”. The issue may lie in the fact that, unlike WSJ, The Times is a news outlet and charging a subscription seems to be in conflict with the primary goal of journalism: educating and informing the public.

However, paywalls are essential to the industry survival. Few people realize that most newspapers still receive the bulk of their revenue from the print product. Advertising revenues have been declining steadily over the past few years, with online readers oversaturated with digital ads (and software like ad-blockers on the rise).

The facts speak plainly: following the implementation of the paywall, the New York Times Company recorded a revenue increase totalling $63 million in 2012. The Gannett’s revenues reached almost $40 million after they began charging readers a subscription for access. For many, implementing a monthly subscription model is not only means to increase revenues but the only way to ensure their survival. The Times’ advertising revenue dropped 8.2% to $737 million, and circulation and subscription revenues are on the decline as well. At the same time, a 2013 Newspaper Association of America’s report highlighted that circulation revenues increased by 5% for dailies, and digital-only circulation revenues skyrocketed by 275%, largely due to the implementation of paywalls. The early adopters of the subscription trend have benefitted the most, and not only in terms of increased revenues. The WSJ registered only a 15% decline in their print circulation in the 15 years following the implementation of the paywall, and even smaller papers like the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette (who introduced their paywall in 2002) have not been hit as hard by the decline in circulation.

What’s more, paywalls are only fair – there’s no such thing as a free lunch afterall. As readers have grown accustomed to paying for digital content when they catch up on their favourite series or listen to music, it makes sense that newspapers are reimbursed for the effort, time and money they put in their pieces. These articles are written by people who often make phone calls, interview people and travel to distant locations to obtain source information and ensure a wide range of perspectives.

Of course, questions and concerns do remain but paywalls are, in their essence, a good thing for the newspaper industry. For the biggest “players” in the newspaper industry, they are a way to maintain print readership and build a digital subscription base, monetizing their global readership in a healthy and sustainable way. By introducing subscriptions, they can ensure the quality of the content, and continue to reimburse their writers, reporters, and journalists for the effort and time spent. The content found in newspapers cost money to produce so it’s only fair that readers will need to pay money to gain access to it, whether they consume it in a digital or print form. Paywalls are changing journalism and at a rapid pace but subscription models are not only an honest revenue source – they are a must for the professional news industry to survive.